Cinema as Historical Archive?

Representing the Holocaust on film

Presented at the IPP conference 2006, University of Mainz (GER)

Note:

To reflect on historical, social and political events could be considered

the 'duty' of the audiovisual media, in particular narrative television

and cinema. The great success and the influence of programmes and films

such as HOLOCAUST and SCHINDLER'S LIST on public opinion about historical

events prove that the worldwide audience is more open for fictionalized

history

than for more challenging documentary work, like Claude Lanzmann's SHOAH.

This poses the question: Has cinema finally reached the status of an historical

archive for some audiences. If this is the fact it would be the goal of

film studies to analyse the specific value of such representations, especially

in the case of a significant phenomenon, like the according to Lanzmann

'un-filmable' Holocaust. The findings of such an analysis may well be

trivialization and not representation of history. In my article I will

attempt to break down the history of holocaust cinema into several phases

and take a closer look at recent films like THE GREY ZONE (2002) that

effectively challenges many of the rules set by former 'Holocaust-cinema'

- and offers a new perspective on a topic that usually only regenerates

established images.

*

Significantly it was by no means the historians, who made

the decisive contribution to the long term establishment of the problematic

term ‘holocaust’ – and the crimes connected therewith

– in both the European and the north American collective consciousness

and memory. They may have critically researched sources, documented their

findings, published textbooks and produced documentaries on and around

the topic, but when compared with the effect by one television melodrama,

a family saga, staged in the midst of vicious of Nazi-war-crimes, suddenly

their efforts seem to have little value other than that of confirming

the historical accuracy of the scenes of persecution and extermination

of ‘imaginary’ figures. The four part television show Holocaust,

whose transmission in 1978 was followed by around 100 million viewers

in the U.S.A , was seen in West-Germany one year later by an audience

of 16 million . From a media-historic perspective, the television event

Holocaust can be described as a decisive point in the social roll of television

as a medium of mass communication. Knut Hickethier comments on the effects

the series had on the formatting of public television as follows:

“The defining television event at the end of the 70’s was

the transmission of the American series “Holocaust” (1979),

which showed the murder of European Jews by the Germans. In setting its

focus not on social criticism and resolving the past but rather on fictionalisation

and entertainment this film marks a turning point (...) The success was

considerable, and uncontested. The series was accused of emotionalising,

trivialising, and falsifying history”.

In Germany, Holocaust made a lasting, one could almost say the first,

deep impression, especially on the sons and daughters of the perpetrators.

The fact that this impression can be traced back to the transmission of

a commercial television mini-series, which intentionally slipped under

the customary ductus of distanced impartiality, has to be seen as an important

indication of a strong change in the social and medial handling of history

in general and the history of the genocide of the third Reich in particular.

From then on the mass-extermination practiced under the Nazi regime had

a name, which everyone knew. At the same time the expression of sober

documentation of the complex topic was unavoidable in order to further

develop the staging of scenes in successful socio-dramas.

The lasting effect of this phenomenon can still be seen today, especially

in the many ‘made-for-the-box office’ cinema films of the

1980’s, which attempted to cash in on the success of Holocaust.

Parallel to the change in the televisual handling of this sensitive topic

it is also possible to trace a general change in attitude towards the

subject: Cinema: Films were produced purely on the basis of the commercial

and aesthetic considerations of the entertainment industry (dramaturgy,

imagery, casting in conjunction with Hollywood’s star system). The

fact that among these, there were also productions, which, by means of

a complex narrative and the more considered use of forms of expression,

left television far behind them, can be seen in films such as Alan J.

Pakula’s Sophie’s Choice (1982). However these more demanding

films also fuelled the debate, which today still questions the legitimacy

of ‘artistic’ processing of the Nazi genocide. According to

Matías Martínez, art cannot possibly ignore the largest

crime of the twentieth century, yet at the same time such art is essentially

impossible, “(...) because in the opinion of many, the holocaust,

defies aesthetic portrayal, in a special, perhaps even unique, way”.

In this respect Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993)

marks a turning point. As in its case, the questionable symbioses between

commercial and the ethical production is widely acknowledged, by both

the public and critics, to have been a success. ”Unlike Marvin Chomskys

and Gerald Greens Holocaust the Hollywood film seemed, in the opinion

of the critics, to have resolved the conflict between popular reception,

aesthetic content, and appropriate thematic” . Schindler’s

list can also be seen as a turning point in another respect. If one looks

at the film as a social phenomenon (which it unquestionably was and is),

various modes of interpretation present themselves, two of which will

be referred to here.

Firstly, one can speculate that in the film Schindler’s List a trend,

which started in the 70’s with the mini-series Holocaust, came to

a provisional end in the 90’s: Little by little a culture of remembrance,

which attempted to find access to the events and environment of Nazi terror

by way of fictional film and always searched anew to defining methods

of staging, established itself next to that of the immediate witnesses

of the concentration camp terror, the victims and the perpetrators. However,

because the witnesses are now increasingly withdrawing from public life,

both new and old films need to be critically analysed regarding intention

and principle.

Secondly the arrival of Schindler’s List made clear the importance

of film as an archive, whose influence on the formation identity in present

day culture is ever growing.

If we accept that film, as an archive, exists as a threshold between the

cultural and communicative/collective consciousness, only by way of the

critical reflection of the viewer and discourse about old and new films,

then this paper can be understood as a proposal for the critical handling

of the film as cultural archive.

The representation of Nazi genocide in the form of feature films is a

subject which has already been widely discussed and documented. As one

can imagine, the filmic representation of events under the Nazi occupation

developed sluggishly at first, then feeling its way, underwent several

‘experimental’ phases, until by the end of the 1970’s

it had developed into a form of filmic mediation which could be compared

to ‘Auschwitz literature’, in which a unique iconography of

genocide and the concentration camp developed. This process of development

ended, in effect, with the television series “Holocaust”,

even here it is necessary to look from the cinema to the television in

order to be able to take all relevant intermediate interaction into account.

This instructive overview covers all films after 1945 which explicitly

handle the events of the holocaust, not films which merely busy themselves

with the Nazi regime (or came in to being earlier than 1945).

The Post-War Years: 1945-1960

Film theorist Béla Baláz remarked in a review,

which was only made accessible after his death, that the polish film Ostatni

etap (1947) by Wanda Jakubowska had founded its own genre, and in so doing

he almost prophetically lent the ‘holocaust film’ an emblematic

character similar to that of ‘Auschwitz literature’. Jakubowska’s

film reconstructs the fate of a group of female prisoners, she utilises

both professional and lay actors, survivors from Auschwitz, who return

to the camps barracks two years after the end of the war. Numerous standard

situations in filmic Holocaust representation are to be seen in the film:

the roll-call, informing on ones fellows, torture, and in particular the

nightly arrival of the prison trains, to swirling flakes of snow or ash

and sludgy muddy ground... Alain Resnais quoted this scene in Nuit et

Bruillard, George Stevens integrated it completely into a nightmare sequence

in The Diary of Anne Frank, and lastly, Steven Spielberg reconstructs

the scene authentically in Schindler’s List. In his essay ‘Fiction

and Nemesis’ Loewy stresses that this film, which reconstructed

these events directly after the historic horror of their passing, is regarded

as an historical document (Fröhlich et al 2003, S.37).

Shortly after the end of the war a German Jewish producer Arthur Brauner

and his CCC-production company produced a film about the Holocaust: Morituri

(1948) by Eugine York. In a sober documentary style the film tells the

story of a group of fleeing concentration camp prisoners and Jewish and

polish families who are hidden in a wood awaiting the arrival of soviet

troops. Parts of the film have an affinity with the novel ‘Das Siebte

Kreuz’ (The Seventh Cross) by the Mainzer author Anna Seghers, which

also tells the story of the flight of seven prisoners, who are hunted

mercilessly by the camp commandant. The commandant has constructed seven

crosses, of which only the seventh remains empty, as one of the prisoners

is successful in his escape thanks to the charity of a handful of villagers.

Fred Zinnemann had already directed the un-pathetic feature film The Seventh

Cross in 1944, with Spencer Tracy in the lead, the film was however first

shown on German television in 1972.

With regard to the concentration camp system, one of the most important

filmic documents of the 1950’s is not a feature film but rather

an essay film. In Nuit et Bruillard/Night and Fog (1953) Alain Resnais

cuts material which he himself produced together with scenes of the liberation

of the death camps, in which masses of dead were found and filmed by allied

troops. In his very subjective, poetic film Resnais established a technique

which is also of importance for later holocaust-film: ‘meaningful

montage’, which reflects on the connections between history and

memory, between past and present. In this respect the influence of this

widely screened non-fiction film upon later fictional cinema films is

not to be underestimated.

Orientation: The 1960’s

One of the most drastic and effective stories of a prisoners

fate is the Italian film Kapo (1960) by Gillo Pontecorvo: Susan Strasberg

plays a young Jew, who ‘rises’ to the rank of warden or ‘Kapo’

in the camp system and from this position torments her fellow prisoners.

The film portrays the woman’s moral dilemma in uncompromising images.

Kapo shows the painful dehumanisation of the prisoners so vividly in order

to make the point that survival in an extreme situation is often contingent

on the suffering of our fellows. Sadly, because the director died in an

accident while still filming, only fragments of Andrzej Munks Pasazerka/the

passenger (1961/1963) remain: On a cruise a former Kapo-woman recognises

one of the passengers as being a former prisoner. The film was presented

in the cinemas as a mixture of film sequences and photographs. A tragic

monument, from which one gets the impression that this was the most ambitious

attempt to handle this theme up to now – by means of a complex montage

this film was to interweave past and present.

In 1963 in the DEFA studios Frank Beyer filmed Nackt unter Wölfen.

Based on the novel by Bruno Apitz the film handles an episode of uprising

in the Buchenwald concentration camp in which political prisoners successfully

manage to hide a child. Beyer’s film places the roll of the political

prisoner in the forefront, especially in the uprising and in so doing

cultivates a so called ‘socialist realism’. According to East

German critics in stead of ‘martyrdom’ he presents the story

of a successful uprising against tyranny. West German critics however,

reacted more sceptically, remarking on the one sidedness of the action

and the one dimensional virtuousness of the resisting prisoners. It is

clear that in this case one can not speak of a realistic representation

of events.

Sydney Lumets dark New York city drama The Pawnbroker (1965) tells the

story of the Jewish pawnbroker Sol Nazerman (Rod Steiger), who is haunted

by his memories of the concentration camp, which mix themselves with his

present (a gang war). Lumet’s film was, aside from the passenger,

the first holocaust film to mixes the past and present by way of ‘meaningful

montage’ (Anette Insdorf), a dramaturgic technique which was often

used in later productions to add an air of authenticity. One can find

a similarly structured use of flashbacks in Karl Fruchtmanns television

film Kaddisch nach mein Lebenden (1969): the plot centres on the trauma

suffered by the protagonist, who was tortured by a fellow prisoner. The

man, who later lives in Israel, becomes analogous with the viewer, an

affected witness plagued by memories of past injustice. The director also

dedicated later works to the discussion of the destructive effects of

an ideology on the individual.

Scandal and Experiments: The 1970’s

The 70’s were, an extremely productive decade for

many nation’s cinemas,: the seed of former revolutionary years began

to grow and brought forth astounding film productions in America (New

Hollywood), Germany (New German Film) and in Japan (New Wave). With this

new progressive tendency and the simultaneous relaxing of censorship came

an enormous wave of exploitation films, which began to push the boundaries

of the portrayable in the direction of sensationalist

entertainment. This exploitative trend did not even shy away from

the holocaust theme: with the Canadian productions Love Camp 7 and Ilsa,

She-Wolf of the SS (1974) the pornographers Robert Lee Frost and Don Edmonds

brought the so called Sadiconazista-films to the cinema. Italian cinema

also experimented with the connections between sexuality, politics and

history, albeit on a higher level. In her psychodrama Il portiere di notte/The

Night Porter (1973) the former documentary filmmaker Liliana Cavani further

develops some realisations from her previous series on the third Reich,

and tells the story of the fatal re-meeting of an SS man (Dirk Bogard)

and his former fantasy victim (Charlott Rampling). As the couple re-start

the destructive relationship under now different circumstances, they land

on the execution list of a group of SS veterans, who wish to remove all

witnesses to un-pleasantries, in order to erase the past and, in so doing,

their own guilt. Cavanis film is both the representation of the continuing

Nazi mentality following the war and (arguably) an attempt at a psycho-sexual

adaptation of the concentration camp system Although Paolo Pasolini’s

modernised Marquis-de-Sade adaptation Salò/120 Days of Sodom (1975)

is rather a film about the fascist Italy of the present day, in this apocalyptic

scenario Paolo Pasolini has constructed an oppressive microcosm of the

concentration camp system, which was only really understood when the film

was recently re-shown in cinemas. Here the mechanisms of power and production

have liberated themselves and are running amok in the collapsing fascist

republic of Salò. The scandalous success of these three films also

inspired the production of a series of concentration camp sex-films in

Italy.

A rare satirical production, the East German comedy Jakob der Lügner/Jakob

the Liar (1974) by Frank Beyer appeared in the mid-seventies. It tells

the story of a Jewish man (Vlastimil Brodsky) who creates and spreads

rumours about the advances of the Red Army, in the Warsaw ghetto, thus

strengthening the hopes of the ghetto inhabitants. The criticism against

the film was directed towards the ambivalent effect of Jacobs lies, which

were thought to placate the ghetto inhabitants with a feeling of security

and therefore cripple their spirit of resistance (Anette Insdorf).

One of the most consequential feature film portraits of a perpetrator

is Götz Georges presentation of the Auschwitz Commandant Rudlof Höss

(here: Friz Lang) in Theodor Kotullas Aus einem Deutschen Leben (1977).

The film shows key episodes from Höss’s biography, his journey

from being a Freikorpsman to the SA and SS and up to the war crimes tribunal,

which sentenced him to death. With a distanced and minimalist coldness

we are shown the inhuman rationality with which he organised the gassings

in Auschwitz. Here the representation concentrates on the perpetrator

and shows the unimaginable horror from a distance. Breaks are found in

single moments, such as when Himmler’s eyes meet those of a prisoner

and then look nervously away.

An iconography of it own: The 80’s

The most important impetus for intensive media discussion

of the holocaust thematic was the four part American television series

Holocaust (1978) – a term which was used to describe the Nazi genocide

against the Jews in particular, and later became synonym for this genocide.

Marvin Chomsky’s epic series follows the fortunes of two families

in the third Reich both on different sides of the genocide: the Jewish

family Weiss and the German family Dorf. Where as one family has to flee,

and is deported, Eric Dorf (Michael Moriarty) joins the SS and becomes

implicated in organising the holocaust. The series was criticised for

its melodramatic and oversimplified structure, which clearly followed

the successful family epic Roots, which told the story of the enslavement

of Africans in the southern states of the USA. Regardless of its trivial

aspects the series Holocaust made a massive impact, comparable only to

that of Spielbergs Schindlers List, and must therefore be recognised as

a milestone in holocaust dramatisation.

The block buster Sophie’s Choice (1982) by Alan J.Pakula is another

film which makes use of the concept of ‘meaningful montage’.

A melodrama about the polish catholic Sophie (Meryl Streep) who survived

a concentration camp because she attracted the attention of an SS officer,

who then posed her the question, which destroyed her life: he asked to

choose which of her children should be spared death. The film tells of

this harrowing event by way of long flashbacks from the midst of its melodrama

structure. As in Il portiere di notte the victim is not of Jewish origin,

Sophie is even able to secure herself a special position by stressing

her Christian heritage. Palukas film reconstructs the scenes of the concentration

camp in faded, monochrome images, a style which, can be seen as an own

iconography and was later adopted by other productions, occurring sometimes

as ‘an empty quotation devoid of meaning ’(Matthias N. Lorenz)

e.g. recently in Brian Singer’s X-Men (2000).

With an elaborate and in places naive naturalism the Arthur Brauner production

of Europa, Europa from Agnieska Holland focuses on the story of a Jewish

boy’s spectacular escape, he first find sanctuary with the communists,

then with the Nazis and finally he is educated in a Napola (national political

educational institution), until it is dismantled at the end of the war.

Unlike Volker Schlöndorffs pathetically simplified Michel Tournier

adaptation Der Unhold / The Ogre (1998), Holland’s film is, alone

by means of its fable/story, able to distance itself from the dark fascination

of the re-staged Nazi spectacle.

After Schindler’s List: The 1990s

In the early 1990’s all filmic work on and around

the holocaust stood in the shadow of Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s

List (1994). Liam Neeson plays the industrialist Oscar Schinlder, who

saves the lives of several hundred prisoners in Poland, by giving them

work in his factories. Spielberg shows the relationship between the socialite

Schindler and the concentration camp commandant Amon Göth (Ralph

Fiennes) as an ambivalent almost dialectic relationship. In an interview

the director describes Göth as being “the shadow which Schindler

cast”. The film makes use of elaborate historical reconstructions

of ghetto and camp life, but never the less concentrates the events of

the film on a few key figures, which brings its melodramatic structures

to the fore front. The use of typical Hollywood ‘thrill’ scenarios

(such as the ‘selection’ or the march to the shower room)

were widely criticised, that said, few other films have managed to awake

such broad public interest for this historical event. Another ground for

controversy was that the ‘Shoa’ foundation, which was financed

from the films profits, was also responsible for the collection of eyewitness

accounts world wide.

Four films of the nineties dealt wit the Holocaust thematic in a comical

way: La vita bella / Life is beautiful (1998) by Roberto Benigni can be

partly taken as a remake of Jakob der Lügner, which was also re-made

by the American director Peter Kassovitz as Jakob the Liar (1999) with

Robin Williams in the title roll. In Michael Verhoeven’s Mutters

Courage (1995) we are told, by means of brechtian meta-reflection, the

tragic-comic story of the mother of poet Georg Tabori, who himself appears

as narrator. The mother survived the Jewish deportations by managing to

win the favour of an SS man. In Train de vie (1998) by Radu Mihaileanus

the prisoners apparently deport themselves in order to escape persecution.

However in the end the whole story is revealed to have been no more than

a camp prisoners fantasy. Due to its bitter end this film can be seen

as the darkest of the ‘holocaust comedies’.

The present day

Following Schindlers List only one ambitious feature film has succeeded in creating a convincing Warsaw ghetto drama: The Pianist (2002) by Roman Polanski tells of the historic events surrounding the suffering, fighting and death in the ;forbidden zone’, from the extremely personal point of view of the Jewish pianist Szpilman (Adrain Brody). In this mature work Polanski creates a mostly un-pathetic reconstruction of this human drama, which does not shy away from the protagonist’s physical deterioration. At around the same time Tim Blake Nelsons film Grey Zone (2002) using the typical New York actor troupe (Harvey Keitel, Mira Sorvino, Steve Buscemi) recreates the story of the Jewish ‘Sonderkommandos’ in Auschwitz. For the first time in a Hollywood-production Nelson creates images according to eye-witness-account that no film before dared to present: the privileges of the Sonderkommandos, they dinner meals with red wine, people having a break on stairs outside the crematory, the green lawn around the crematory being watered artificially. These images – although historically correct – seem cynical, artificial, metaphoric. But yet this film may be closer to the fact than Schindler’s List. For the average viewer Spielberg’s film seems more accurate simply because his sharp edged black and white images are congruent to the image-archive the film- and media-industry has reproduced so far. Images of images seem more historical than accurate reconstruction. Being the opposite of The Grey Zone, another film falls in every trap on the way: Jeff Kanews Babij Jar (2002) should have been the glorious finale of Arthur Brauners work on the holocaust, however through its simple structures and stereotypical staging the film hardly even portrays this unimaginable massacre, in which over 30,000 people were killed in two days. “To show, how it was“ does not mean mixing the documentary with the fictive – as this film does -, neither does it mean recreating an historical event by means of media influenced images. To really be able to create an impression of the ‘horror’ still requires artistic vision, a gift, pars pro toto, to find sounds and images for an event, which one hardly dares to imagine. Film history contains such portrayals, of such events, but they are rare and must be attempted and re-attempted. For that reason the chapter on the artistic portrayal of ‘an imagined place of horror and suffering’, is a long way from being at an end.

Literature:

Agamben, Giorgio (2004): Ausnahmezustand. Frankfurt a/M.

Agamben, Giorgio (2003): Was von Auschwitz bleibt. Das Archiv und der

Zeuge. Frankfurt a/M.

Assmann, Jan (1997): Das kulturelle Gedächtnis. Schrift Erinnerung

und politische Identität in frühen Hochkulturen. München.

Foucault, Michel (1983): Der Wille zum Wissen. Sexualität und Wahrheit

1, Frankfurt am Main 1983

Fröhlich, Margrit und Hanno Loewy, Heinz Steinert (Hrsg.) (2003):

Lachen über Hitler – Aschwitz-Gelächter? Filmkomödie,

Satire und Holocaust, edition text + kritik

Früchtl, Josef u. Zimmermann Jörg (2001): Ästhetik der

Inszenierung. Dimension eines gesellschaftlichen, individuellen und kulturellen

Phänomens. In: Josef Früchtl u. Jörg Zimmermann (Hg.):

Ästhetik der Inszenierung. Dimension eines gesellschaftlichen, individuellen

und kulturellen Phänomens. Frankfurt a/M. 9-47.

Goetschel, Willi (1997): Zur Sprachlosigkeit von Bildern. In: Manuel Köppen

u. Klaus R. Scherpe (Hg.): Bilder des Holocaust: Literatur – Film

– Bildende Kunst. Köln, Weimar, Wien. 131-144.

Halbwachs, Maurice (1985): Das kollektive Gedächtnis. Frankfurt/M..

Hobsbawm, Eric (1996): Wieviel Geschichte braucht die Zukunft. München.

Hickethier, Knuth (1998): Geschichte des deutschen Fernsehens. Stuttgart,

Weimar.

Insdorf, Annette (1983ff.): Indelible Shadows. Film and the Holocaust,

New York: Cambridge University Press

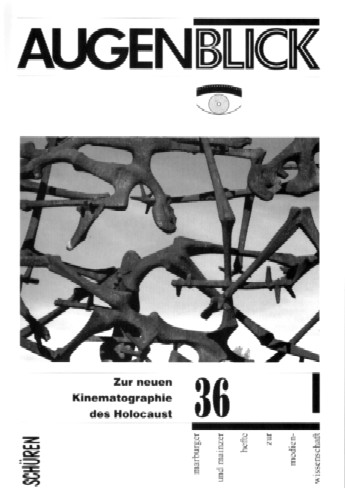

Jackob, Alexander and Marcus Stiglegger (ed.) (2005): AugenBlick 26: Zur

neuen Kinematographie des Holocaust. Das Kino als Archiv und Zeuge?, Marburg:

Schüren

Junker, Detlef (2000): Die Amerikanisierung des Holocaust. Über die

Möglichkeit, das Böse zu externalisieren und die eigene Mission

fortwährend zu erneuern. In: Ernst Piper (Hg.): Gibt es wirklich

eine Holocaust-Industrie? Zur Auseinandersetzung um Norman Finkelstein.

Zürich, München. 148-160.

Koebner, Thomas (2000): Vorstellungen von einem Schreckensort. Konzentrationslager

im Fernsehfilm. In: T.K.: Vor dem Bildschirm. Studien, Kritiken und Glossen

zum Fernsehen, St. Augustin: Gardez!, S. 73-91

Köppen, Manuel (1997): Von Effekten des Authentischen – Schindlers

Liste: Film und Holocaust. In: Manuel Köppen u. Klaus R. Scherpe

(ed.): Bilder des Holocaust: Literatur – Film – Bildende Kunst.

Köln, Weimar, Wien.145-170.

Kramer, Sven (ed.) (2003): Die Shoah im Bild, edition text + kritik

Martinez, Matías (1997): Authentizität als Künstlichkeit

in Steven Spielbergs Film Schindlers List. In: Compass. Mainzer Hefte

für allgemeine und Vergleichende Literaturwissenschaft. Nr. 2. 1997.

S. 36-40.

Novick, Peter (2001): Nach dem Holocaust. Der Umgang mit dem Massenmord.

München.

Hübner, Heinz Werner (1988): Holocaust. In Guido Knopp u. Siegfried

Quant (Hg.): Geschichte im Fernsehen. Ein Handbuch. Darmstadt. 135-138.

Ravetto, Kriss (2001): The Unmaking of Fascist Aesthetics, Minneapolis:

The University of Minnesota Press

Stiglegger, Marcus (1999/2002): Sadiconazista. Sexualität und Faschismus

im Film, St. Augustin: Gardez!

Remark: Some of this article is based on the book

A. Jackob & M. Stiglegger (Hrsg.)

Zur neuen Kinematographie des Holocaust

Das Kino als Archiv und Zeuge? (Augenblick Band

36)

Schüren Verlag: Marburg 2004, 7,90 Euro

Thanks to David Bucknell for translating most of the text.